Long before the Civil War, dentists recognized the critical need for oral care in the military. When the American Dental Association (ADA) was established in 1859, its founders could not have foreseen how soon these concerns would become urgent. Over the next 90 years, dental professionals served both in wartime and peacetime, advocating for the importance of dental health on the battlefield, and lobbying for and receiving a formal military presence.

“Dentistry at the Front Line” highlights the evolution of military dentistry, showcasing the work of dentists in wartime and the pivotal efforts that transformed dental care for service members and shaped the role of dentistry in the modern armed forces.

Civil War to Spanish-American War

The outbreak of the Civil War in the spring of 1861 focused the dental profession's attention on what had become a long-standing concern of the ADA: military services and dentistry. Dentistry in the armies of the Civil War was more of an afterthought than a profession. Recruits were rejected for having bad or no teeth, because a solider in combat had to be able to tear open with his teeth a paper wrapper containing ball, powder, and wadding for his muzzle-loading rifle.

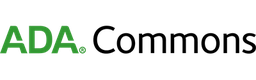

Army surgeons were attached to both armies during the war and generally extracted teeth and lanced boils on the gums of patients. Soldiers in need of having cavities treated or rudimentary oral surgery typically went to see a civilian dentist, either in a fixed base camp or in a large occupied community such as Chattanooga or Atlanta.

The Confederate Army was probably more progressive in its treatment of dentists and dentistry than the Union Army. There were only about one thousand dentists in the southern states and only 10 percent had received a formal dental education. The Confederate Army conscripted dentists, who were assigned to base hospitals where they were called upon to perform oral surgery, a near necessity at a time when face and jaw wounds were among the most common wounds suffered by soldiers on the battlefield.

Military dentistry was the topic of the 1864 meeting of the ADA at Niagara Falls. (See image above right.) Dr. Samuel S. White reported that he had discussed military dentistry in a meeting with President Abraham Lincoln earlier in the year. White later spoke to the acting surgeon general, who said that nothing could be done while the armies were in active operation, but perhaps something could be accomplished when the armies went into winter quarters.

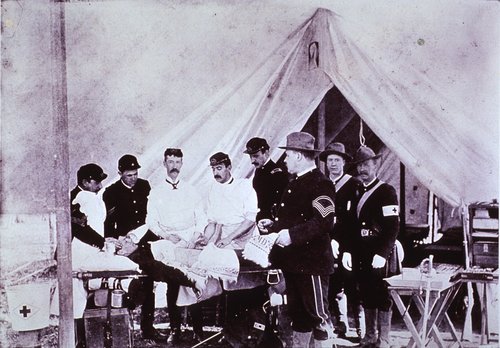

However, nothing would be done until the Spanish-American War, more than thirty years later, when the sad shape of dental health of most American recruits was revealed. It was not until 1901 that President William McKinley signed legislation establishing a dental corps of thirty contract dentists within the United States Army.

Dentistry in WWI

While the establishment of a small dental corps was an accomplishment for the field of military dentistry, the profession realized that more was needed to provide the level of care required across the armed forces. After the turn of the century, the ADA continued to lobby for the establishment of a separate military dental corps, staffed with dentists of officer rank.

After many years of lobbying efforts (see also: Dr. Williams Donnally in "Honoring the History Makers"), President William Howard Taft signed legislation to establish the Army Dental Corps, Navy Dental Corps, and Navy Dental Reserve Corps between 1911 and 1913.

During the war, army dentists treated nearly 1.4 million soldiers, in every kind of camp and condition, from modern post-dental clinics in the United States, to primitive facilities in the trenches of France. Military dentists helped reconstruct the faces and jaws of thousands of wounded soldiers, sailors, and marines. Moreover, seven army dentists and seven army dental assistants were killed in combat.

World War I proved beyond a doubt that dentistry was critical to the health and well-being of the recruits in the modern army and navy. Military dentists had proven their worth. The War Department integrated dentistry into the regular army during the early 1920s. In 1920, the army created the Dental Reserve Officer Training Corps, and in 1922, opened the Army Dental School in Washington, DC.

Seeking Recognition: 1918-1940

Legislation of the first World War established the framework for dental officers, but additional work needed to be done. The Act of October 6, 1917, granted army dental officers equality in rank and other privileges with officers of the Medical Corps. Navy and Marine Corps dentists partially attained this status in 1918. The same act established the proportion of one dental officer per thousand military personnel. This ratio, adopted also for the navy, remained the basis for determining the size of the Dental Corps through most of the years between WWI and WWII.

During the 1920s, the ADA devoted considerable effort to seeking an increase in the ratio of dentists to military personnel of one to five hundred. It also endeavored to raise the ceiling on the rank to which dental officers could rise. This effort was caused in part by the desire to enhance the prestige of dental officers, but also to secure rewards for length of service, and to furnish an incentive for dental offices to remain in uniform.

These efforts were generally unsuccessful at the time. Agitation on the part of the ADA for increases in the pay schedules of dental officers was denied as government expenditures were cut during the 1920s. Similarly, retrenchment to combat the Depression meant the threat of reducing the size of both the Army and Navy Dental Corps, as well as the continued services of reservists on active duty. Representatives of the ADA worked to salvage the careers of these officers and struggled to maintain the accomplishments prior. This continued until the late 1930s, when the country began restoring military capability.

By 1940, the U.S. government had requested assistance from the ADA to procure dental officers to serve the expanding armed forces, while maintaining the necessary minimum of dental care for the civilian population (a concerning issue that arose during the previous war). The ADA accepted the responsibility gladly in order to best represent the needs of dental officers in service and later support them on their return to civilian life.

A New Future for Military Dentistry: WWII

More than twenty-two thousand dentists served their country in WWII and many lost their lives. They served in all branches of the armed forces and on far-flung war fronts around the world. Dentists also served on the home front. Dental offices back home were crowded because of the great number of dentists serving their country. Dentists coped with wartime shortages of silver, gold, and other materials. Dentists and their staffs wrapped bandages for Red Cross packages, participated in scrap metal drives, and invested part of their paychecks in bonds to help finance the war.

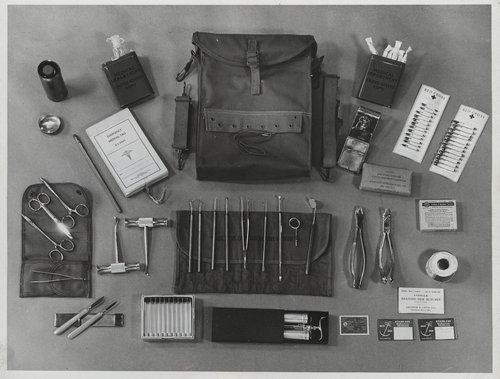

The ADA could not hold an Annual Session during 1945 due to wartime travel and resources restrictions, but it remained active throughout the war years. The Association worked closely with the U.S. military to access wartime dental needs and successfully lobbied Congress and wartime regulatory agencies for the same extra gasoline rations that the nation's physicians enjoyed. In addition, the ADA and state dental organizations were instrumental in outfitting mobile dental units for the use of the troops in combat zones.

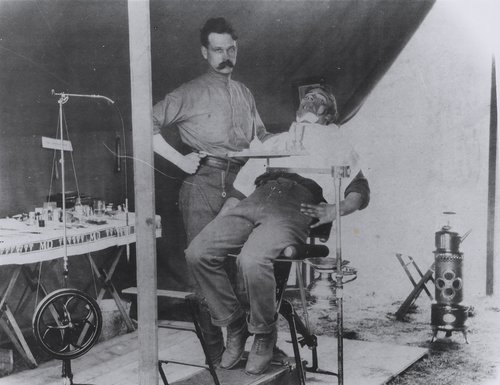

Young American men, it turned out, were not an especially fit bunch as our country entered the war, In June 1941, even before the U.S. entered the war, the Selective Service reported that three hundred eighty thousand men out of the one million registrants who took the Selective Service physical exam failed to qualify physically for military service. The leading deficiency: 17 percent of those who failed their physicals did so on the basis of their teeth. Indeed, failure to meet the minimum standard of having six opposing teeth was a leading cause of rejection from military service in both world wars, just as in the previous century.

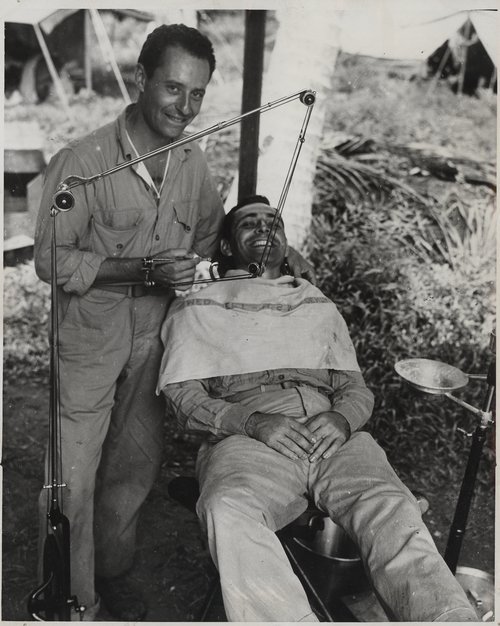

Dentists served all over the globe and many faced the same discomforts and dangers as the frontline troops. U.S. military dentists practiced their profession at places like Guadalcanal, the Kasserine Pass, Anzio, and the Huertgen Forest, often under difficult conditions. They restored teeth and did complex oral surgery in mobile dental units or makeshift operatories in tents that were often the targets of enemy shelling or aircraft attacks. At Pearl Harbor, on December 7, 1941, two Navy Dental Corps officers were killed, and four others were wounded. In the Pacific theatre, fifty-three American military dentists were captured by the Japanese and held as prisoners of war. A total of twenty-two dentists died as Japanese POWs, a 40 percent mortality rate.

Thousands of young men who served combat tours of duty with fighting units—armory, infantry, artillery, fighter planes, and battleships—were future ADA members. They returned to the United States following the war to earn college degrees on the GI Bill, went to dental school, and opened practices in the late 1940s and 1950s.

Resources and Ways to Learn More

American Dental Association. 150 Years of the American Dental Association: A Pictorial History, 1859-2009. Donning Co. Publishers, 2009.

McCluggage, R. W. (1959). A history of the American Dental Association; a century of Health Service. American Dental Assn.

The Journal of the American Dental Association, 125th anniversary commemoration, 88(2).

The Role of Expeditionary Dentistry in Large-Scale Combat Operations

A History of Dentistry in the US Army to World War II, Borden Institute

The Dental Corps of the United States Navy: A Chronology, 1912-1987.